President Biden’s “Putin” gaffe was unfortunate. We can do better.

Talking Big Ideas.

“Our new president . . . Hoobert Heever!”

~ Harry Von Zell, flubbing the name of President Herbert Hoover

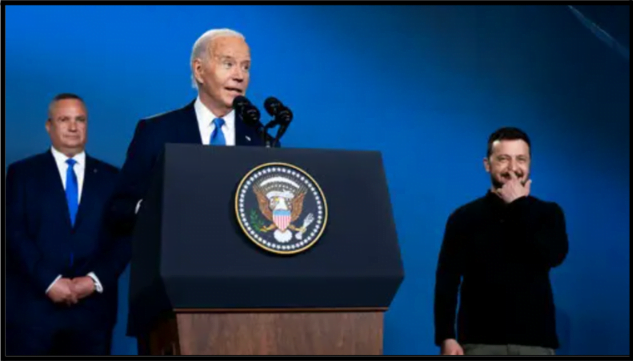

Yesterday, President Biden gave us a textbook example of how things can go wrong when introducing a speaker:

At the NATO Summit, with Ukrainian President Zelensky waiting to take the stage, Biden said: “And now I want to hand it over to the President of Ukraine, who has as much courage as he has determination. Ladies and gentlemen, President Putin!”

Ouch.

Importantly, Biden is not alone. Dale Carnegie taught a century ago that “no speech is more mangled than the speech of introduction . . . most are poor affairs, feeble and inexcusably inadequate.”

This is just as true today. Too often, people don’t consider these quick remarks a speech at all, which is likely why they get botched so regularly. But an introductory speech is absolutely a speech. And one you will likely have to deliver several times in your life. I urge you to take it seriously.

When I work with our clients to prepare introductory speeches, I like to begin by sharing two classic cautionary tales.

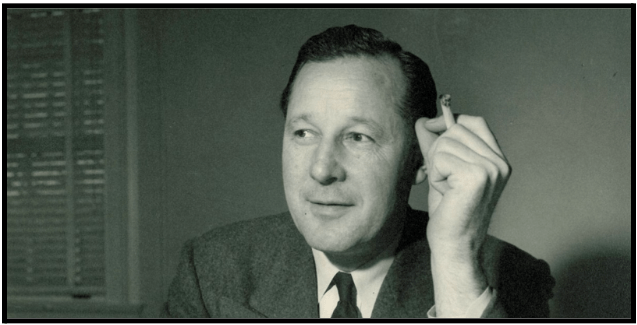

John Mason Brown, a famous mid-20th century writer and speaker who traveled the country keynoting conferences, writes in his book Accustomed As I Am about a time he was backstage listening as the host quieted the audience down and delivered these remarks:

May I have your attention, please? We have bad news for you tonight. We wanted to have Isaac Marcosson speak to you, but he couldn’t come. He’s sick. [awkward applause]

Next we asked Senator Bledridge to address you. But he was busy. [awkward applause] Finally, we tried in vain to get Doctor Lloyd Grogan of Kansas City to come down to speak to you. [awkward applause]

So instead, we have John Mason Brown. [silence]

Brutal! But perhaps an improvement over the introduction that writer Stephen Leacock once received:

This is the first of our series of lecturers for this winter. The last series, as you all know, was not a success. In fact, we came out at the end of the year with a deficit. So this year we are starting a new line and trying the experiment of cheaper talent.

May I present Mr. Leacock.

Poor guy!

When I lived in DC, I went to see a fascinating Nobel Laureate give a speech to a friendly audience. We all had to wait while the introductory remarks droned on in pedantic detail. They were read without eye contact from sheets of paper — with many words butchered — in a completely monotone voice.

The baseline for introductory speeches is low indeed. The audience deserves better. The speaker deserves better. The event team deserves better!

Introductory speeches prime the audience to feel a certain way. Done poorly, they make the audience squirm – or space out. Done well, they get the audience pumped up and excited for the main speech.

The goal of every introductory speech is to sell two things:

the speaker and the topic.

As Stephen Lucas writes in his excellent book, The Art of Public Speaking: “The aim is to make this audience want to hear this speaker on this subject.” Audience + Speaker + Topic. These are the three primary ingredients in every successful introductory speech. I like to put them in this order:

- TOPIC: Clarify what the speaker will be discussing.

- AUDIENCE: Explain why the topic is relevant for this particular audience.

- SPEAKER: Ham up the speaker’s credibility and skill.

To make sure you crush your next introductory speech, consider these guidelines:

DO YOUR HOMEWORK

Begin early. Give yourself time to do research on the topic, audience, and speaker.

Gather more content than you plan to use. Key ideas, stories, and analogies that bring the topic to life in a way that will connect it with the audience. Consider the speaker’s background, qualifications, and expertise on the topic.

Do you have any unique connection to the speaker you can share? Any relevant or surprising insight?

Pull together everything you need “to make this audience want to hear this speaker on this subject.” Consider organizing your remarks like this: Topic → Audience → Speaker.

BE ACCURATE

Triple check everything you say is true.

Consider showing the speaker (or the speaker’s assistant) your remarks in advance. Or at least your basic outline.

Make sure you know how to say the speaker’s name correctly. If there’s any chance the name has an unusual or difficult pronunciation, get clarification in advance.

Run several reps just on the speaker’s name. Get it in your blood so you don’t pull a Hoobert Heever! or a President Putin!

BE BRIEF

When you do your homework, you end up with more content than you’ll be able to use. Trim it down to the best stuff.

Shoot for a minute. No more than two. If you’re close to three minutes, follow Brene Brown’s advice and cut your remarks in half.

BE YOURSELF

You are not allowed to print up a website bio and read it from the stage!

This is your speech. Use your research, delivered in your style and voice. Speak in a conversational tone without referencing notes. It’s hard to excite the audience and build up the speaker’s credibility if you’re reading.

Stay away from jargon and fancy titles. People don’t care that Tyler Cowen is the “Holbert L. Harris Chair of Economics at George Mason University.” They want to hear a cool anecdote about why you think he’s so impressive, and why he is relevant to them.

ADD DRAMA

Have at least one impressive, appealing, or surprising anecdote that you drive home.

Instead of looking at notes, have good eye contact with the audience the whole time. (You’re only speaking for a minute or two.) Use your eye contact and enthusiasm to help focus the audience’s attention and build their excitement.

Save the speaker’s name for your final words. Even when everybody knows who the speaker is, you still build excitement this way. Watch the Biden clip again from above. He does this well:

And now I want to hand it over to the President of Ukraine, who has as much courage as he has determination. [PAUSE] Ladies and gentlemen [NAME]

Pause before saying the speaker’s name, ensuring the audience feels the climax. Say the name while looking at the audience – don’t look down (as Biden does in the clip above), and don’t look at the speaker (which is common).

PRACTICE

Run a few full reps with a coach or trusted colleague. Seek out honest feedback and use it to iterate and polish.

Get to the point you feel comfortable delivering your remarks without looking at your notes. Make sure you cross the Uncanny Valley before stepping on stage.

WRITE YOUR OWN INTRO

Any time you are the main speaker, draft an outline for introductory remarks along with your keynote speech.

Whenever you are being introduced at an event, give the person introducing you a copy of the outline you’d like them to use. Send it to them well in advance. (The better the person knows you, the less content you need to share.)

This will significantly increase the odds that the person introducing you tees you up for success.

***

Follow these guidelines, and I’m confident the audience will get pumped up and ready for the main act.