Talking Big Ideas.

“Shakespeare . . . what a wonderful thief he was.”

~ Mark Forsyth, The Elements of Eloquence

My buddy Tony was waiting backstage to speak at a big event.

Another presenter came over and said to him, “I’ve seen a bunch of your talks. I have to say, I really admire how funny you are. I’m jealous. I wish I could be more like that.”

Tony said, “Do you want to know my secret?”

“Absolutely!”

“The joke I’m going to use tonight I first heard 20 years ago. I didn’t write it. All I do is pay attention to what makes audiences laugh. And what makes me laugh. I save the best stuff I hear, and then I use them in my talks.”

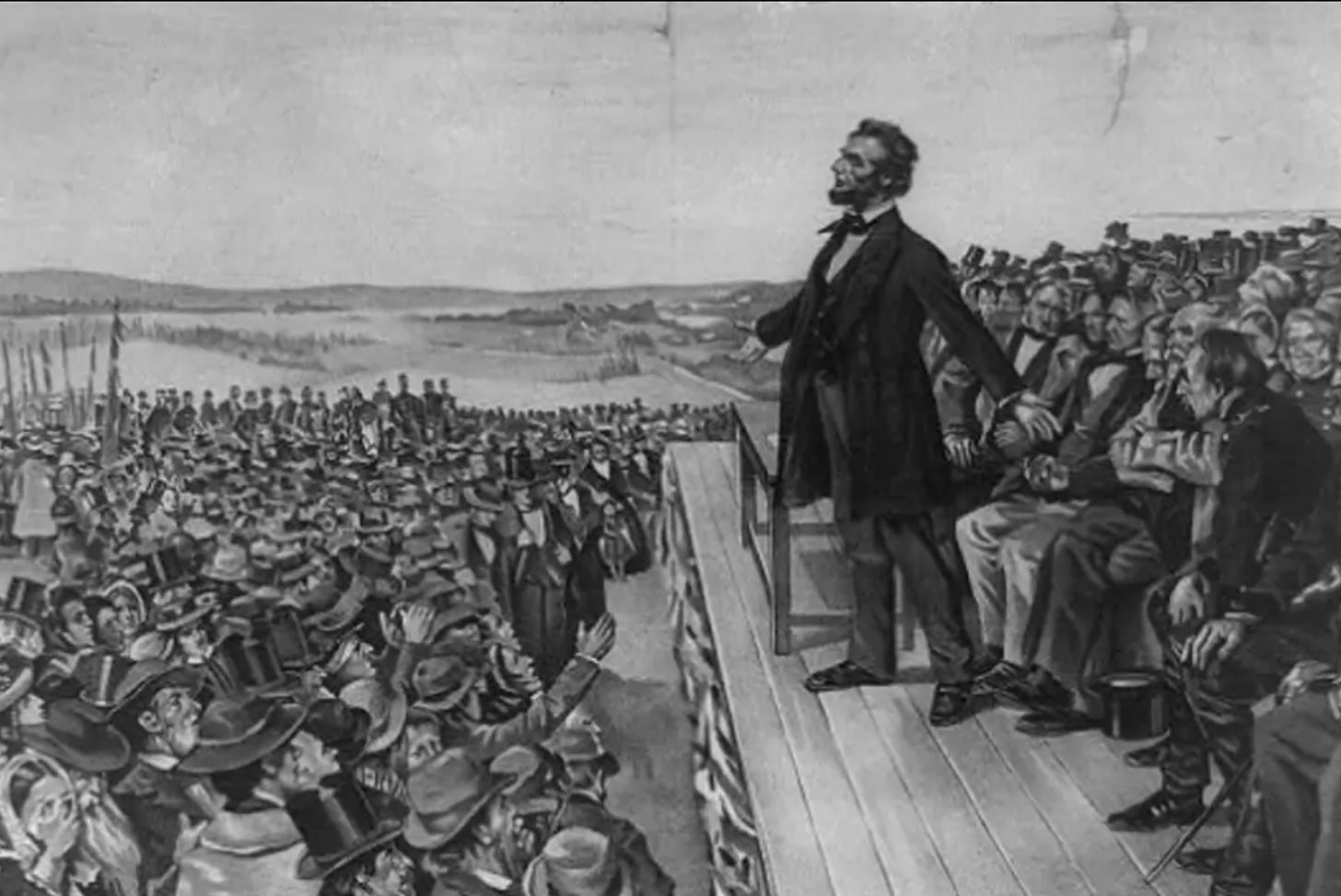

This tactic extends beyond jokes. For example, what’s the most celebrated speech in American history? Two stand out: Lincoln’s address at Gettysburg and King’s I Have a Dream sermon at the Lincoln Memorial.

The Oxford Library in England has the Gettysburg Address cast in bronze to illustrate what can be accomplished with the English language. Perhaps the most memorable line from this most memorable speech is:

“government of the people, by the people, for the people”

It’s super catchy. Even today, many people recognize it. How did Lincoln come up with this phrase?

As it turns out, he didn’t.

Lincoln loved to read. His law partner gave him a book by the minister Ted Parker that includes a speech called The American Idea. Lincoln underlined this part:

“A democracy – that is a government of all the people, by all the people, for all the people”

So it was Ted Parker who came up with Lincoln’s immortal line.

Except he didn’t either. Twenty years before Parker said it, Daniel Webster delivered his Second Reply to Hayne, now lauded as The Most Famous Senate Speech. He included this line: “the people’s government, made for the people, made by the people, and answerable to the people.”

Webster was a world-class orator, so it makes sense the line came from him.

Except, again, it didn’t.

Half a millennium earlier — in the 1300s! — the philosopher John Wycliffe translated the Holy Scriptures to Middle English and wrote in the preface: “This Bible is for the government of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

Wycliffe was a student of history. He knew that more than a thousand years before he was born, a general from the Peloponnesian War stood before the people of Athens and spoke about a ruler “of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

Where did the general discover the phrase? I don’t know, but I like to think it continues to travel back through time, sticking inside countless minds of the distant past.

How about King’s I Have a Dream speech?

It’s steeped in material from other places! His first words, “Five score years ago,” are a slight tweak to Lincoln’s opening at Gettysburg, “Four score and seven years ago.”

King says: “I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made straight . . .”

It’s one of several passages taken straight from the Bible. Here’s Isaiah 40:4-5: “Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill shall be made low, and the crooked shall be made straight, and the rough places plain . . .”

Even his most iconic phrase, “I have a dream,” was lifted verbatim from a speech by the civil rights activist Prathia Hall.

King ends by directly quoting an old spiritual: “Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!”

What about the greatest English writer of all time?

In 1607 Shakespeare published his famous play Antony and Cleopatra. The ancient biographer Plutarch wrote the seminal history of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra. It was translated from Greek to English by Thomas North in 1579.

Here’s the North translation of Plutarch:

she disdained to set forward otherwise but to take her barge in the river Cydnus, the poop whereof was of gold, the sails of purple, and the oars of silver, which kept stroke in rowing after the sound of the music of flutes

And here’s Shakespeare:

The barge she sat in like a burnished throne,

Burned on the water: the poop was beaten gold;

Purple the sails and so perfumed that

The winds were lovesick with them; the oars were silver,

Which to the tune of flutes kept stroke . . . .

Mark Forsyth writes in The Elements of Eloquence: “The thing about this is that it’s definitely half stolen. There is no possible way Shakespeare didn’t have North open on his desk when he was writing.”

The science author Steven Johnson is an expert on innovation. He says in his speech Where good ideas come from that people think new ideas pop up all at once. But the truth is they slowly build and evolve over time. Most new ideas are simply old ideas that have been tweaked or combined:

We take ideas from other people, from people we’ve learned from, from people we run into in the coffee shop, and we stitch them together into new forms and we create something new.

The flow of ideas through history involves the accumulation, adaptation, and improvement of thought as well as the direct borrowing and tweaking of specific phrases and concepts. The same is true for many of our best writings and speeches.

Here’s a simple theme from the Institute for Justice (IJ) that encapsulates a complex lawsuit challenging the licensing of tour guides: They’re just storytellers.

Like Shakespeare, the IJ attorneys clearly drew inspiration from an earlier work – in this case, a previous IJ theme challenging the licensing of casket makers: It’s just a box.

Every workshop Maryrose and I run is uniquely tailored to our specific audiences. Yet most of our content is pulled from material we’ve already used – or at least tested in some way. Even this article is stolen in part from previous pieces I’ve written.

Years ago, I watched the researcher Adam Thierer capture the attention of an entire room of DC elites with his stories. I’ve seen him do this several times since.

His secret: “I save all my best stuff.”

Adam does research on lots of topics and makes a point to find powerful insights, analogies, and stories that bring to life the complex ideas he discusses. Of course, all the insights he shares aren’t pulled from thin air every time he speaks.

The writing coach David Perrell teaches his students the same path Adam took: “like a good investment, the benefits of your note-taking system should compound in value. Save ideas that will stay relevant for many years.” He advises to “trust your notes – not your memory” and you’ll “never start with a blank page.”

The authors Chip and Dan Heath encourage us to become experts in “the art of spotting.” To be on the lookout for catchy ideas, phrases, and stories. And when we find them, to capture and make them our own.

Good spotters, the Heath brothers say, will always have an advantage over even the most incredible creative geniuses. Because spotters can draw from all the best creators in history.

You don’t have to reinvent the wheel for your talks. Spot, tweak, and polish words and ideas from people you admire. The wheel itself was invented six thousand years ago – and then copied, improved, and adapted ever since to fit various environments and terrains.

Little adaptations compound and become fundamental to progress. It’s how biology forms complex life. How markets create wealth. How science advances. And how we build new technologies, skills, and ideas.

As the neuroscientist Ethan Kross says, iteration based on reflection and feedback is “one of the central evolutionary advances that distinguish human beings from other species.”

We all would do well to build off the best ideas and insights of others. But what about plagiarism?

We can ask for permission, as Dr. King did with the phrase I have a dream. We can always quote, paraphrase, or summarize. We can tweak and polish until the words and ideas become our own. And unlike many giants from the past and academics of today, we can be liberal in giving credit.

Whether we build off of ourselves or others, we rarely start from scratch.

Consider that declarations of independence worldwide, from Costa Rica to Hungary to New Zealand, have entire sections drawn from the U.S. Declaration – which itself took many ideas and phrases from George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights.

Mason’s words, incidentally, were “borrowed liberally” from the philosopher John Locke.

Who found them in Baruch Spinoza.