“For how great the pleasure, how great, think you, are the joys of the spirit . . . in wondering at the mighty mass of mountains while gazing upon their immensity and, as it were, in lifting one’s head among the clouds. In some way or other the mind is overturned by their dizzying heights and is caught up in contemplation of the Supreme Architect.”

~ Naturalist Conrad Gessner (1516-1565)

“Ya see that mountain o’er dere? Yea, one of these days I’m gonna climb dat mountain!”

~ Mountain Music, Alabama (1982)

The air was cold in the afternoon on the 11th of April in 2009. My climbing partner Jeff and I were alone, deep in the Nevada desert. I was dangling upside down by a rope, staring at the ground spinning around more than a thousand feet beneath me. I had just taken a long screaming fall and couldn’t figure out how get back on the rock and continue climbing. I tried—doing everything I possibly could—to no avail.

But I had to figure it out. It was our only way off the mountain.

A month earlier we were sitting at a D.C. airport together. It was early, the sun had yet to rise. Our plan was set: fly to Nevada and test ourselves with a long, difficult, rarely done climbing route called Resolution Arete that summits Mount Wilson, the highest mountain in Red Rock Canyon. I had my heart set on it for years.

Bags packed full of climbing gear, we sat at the airport looking at each other, apprehensive and wondering if we’d get to board the plane. We were flying stand-by, a benefit of Jeff’s wife. Turns out, the flights were all booked. Before we could pretend to be upset Jeff quickly pointed out,“I know we’re both secretly relieved about this.” We knew that summiting Mount Wilson would be an enduring test for us. But it would have to wait. We drove back to our homes that morning discussing how we would get to Nevada as soon as possible. A few short weeks later, we’d find out just how tough it is to climb Resolution Arete.

INITIATION

I never would have started climbing if it weren’t for the Supreme Court.

Just before Christmas in the year 2000, while I was in the midst of college out in Ohio, unbeknownst to me a little-known law firm filed a little-known lawsuit in a little-known town in New England. But this law firm had some of the most brilliant legal minds working for it, and their lawsuit would ultimately unleash an explosion of outrage throughout the country, affecting the lives of countless people. Myself included.

The case centered on a simple question: May the government take your home and hand it over to someone richer if that richer person promises to generate more tax revenue with your property? The lawsuit worked its way through the legal system, all the way up to the highest court in the land. And in June 2005, the Supreme Court issued its controversial 5-4 ruling in favor of the government.

The infamous Kelo decision.

People went crazy. The law firm, the Institute for Justice, burst into the national spotlight. Refusing to give up, IJ launched a multi-million dollar campaign, taking the fight to state courts, state legislatures, and the court of public opinion. IJ needed more resources, quick, so it hired several new people. One was an attorney named Jeff. Another was a tall, dark, and handsome young fellow (an entry-level comms assistant: me).

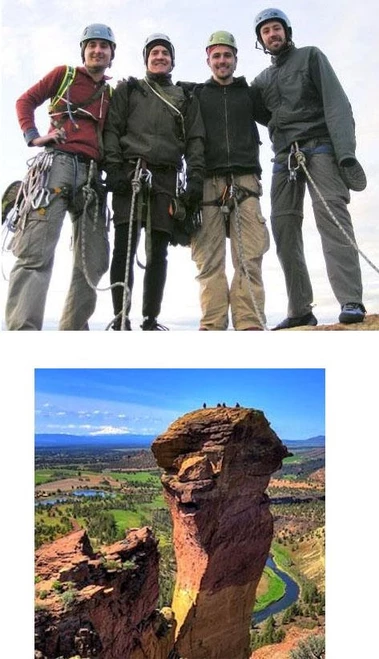

Outside of suing governments, Jeff’s passion was climbing. Moving to a new city meant that he needed a new climbing partner. One of IJ’s production guys, Isaac, just started climbing. After hearing Jeff talk about his adventures, Isaac and I said that we’d like to join him. My brother Scott expressed interest as well. The four of us have been climbing together ever since, summiting vistas around the country and beyond.

15 years after Kelo, 9 state supreme courts, 44 state legislatures, and thousands of media stories have repudiated the high court’s decision—and as an added bonus, I got to meet Jeff and Isaac. Without Kelo, I likely never would have made a career in DC. And I almost assuredly would not have started climbing. I’ve always enjoyed outdoor activities, but had never climbed before. To be honest, I never even thought about it. I didn’t know it was an option.

I DIDN’T KNOW I COULD

Biologist Richard Dawkins opens one of his bestselling books with this:

As a child, my wife hated her school and wished she could leave. Years later, when she was in her twenties, she disclosed this unhappy fact to her parents, and her mother was aghast: “But darling, why didn’t you come and tell us?” Lalla’s reply is my text for today, “But I didn’t know I could.”

I didn’t know I could.

How many things in life do you think this way about? Perhaps even more important, how many things in life do you not even know that you think this way about?

Until I started climbing, I didn’t know I could.

I’ve never been the greatest athlete. Or the best student. Or the hardest working employee. But with climbing, none of that stuff matters. Everyone can enjoy climbing. Show up to any climbing gym on the planet, and you’ll find a diverse array of people: young and old, short and tall, male and female, ripped and flabby, outgoing and shy, atheist and creationist, Democrat and Republican, Capulet and Montague. There will be climbs so easy your grandma can do them, and climbs so hard that no one but Spiderman could ascend them freely. But the motley crue of folks assembled will all be enjoying the gym together.

And notice that with most activities—from traditional sports to martial arts to games like chess—there is a winner and a loser. They are zero sum. But climbing is different. Everyone, regardless of skill level, walks away having gained.

The bottom line is this: In climbing everybody wins. And just about every person who wants to climb can do it. Including you.

I have a quick action item for you to do right now:

Do it. Google Eichorn Pinnacle. Check out the pictures. Find the one that resonates the most with you. Now take a moment to imagine yourself standing there, on the very top. Feel the rock beneath your feet. Feel the cool alpine breeze on your face. Feel the exhilaration deep inside you. Stare at the beautiful vistas that surround you. Watch the sun slip behind a distant mountain. Immerse yourself in the tranquility of the moment.

For years now, I’ve done exactly that. I’ve dreamed of standing on the summit of Eichorn Pinnacle. To be fair, the first time outdoorsy people see Eichorn is like the first time excitable ladies see Isaac Morehouse, the editor of this book: Once your eyes gaze upon that beauty in all its splendor, it’s damn near impossible not to fantasize about!

Here’s a cool truth: You can climb Eichorn Pinnacle.

Crazy as it looks, it’s not a technically difficult climb. There’s no reason you can’t stand on that summit, if you want to do it. You don’t have to be gifted athletically. You don’t have to be brilliant or exceptionally hard working. You don’t need to be rich. You don’t need a lifetime of experience. All you need is a desire to do it, a little climbing know-how, and a capable partner with experience (or a guide) to handle the logistics. It may look impossible, but you absolutely can do it!

And here’s the kicker: if you learn enough about climbing, you can even be the one that leads your climbing team to the summit of Eichorn Pinnacle.

Maryrose and I are going to climb it next time we’re in Yosemite. And it will be amazing.

NEVADA

Jeff and I secured a standby flight to Las Vegas on April 10 in 2009. We checked into a motel, bought food for our climb, packed up everything we’d need for Resolution Arete, and drove into Red Rock Canyon.

It’s easy to get lost in the Canyon. Many climbers end up never finding the route they set out to climb. So we began with a scouting mission. We hiked through the desert for two hours, mostly uphill. We found the path we wanted. When it turned into a rock scramble, we continued up for awhile and stashed our packs under some boulders. Then we hiked out to the car. Back in town we had dinner and went to bed before the sun went down. We woke up at 3:30 a.m. on April 11 and set off for our adventure.

We reached our packs at sunrise and continued to scramble up the rock to the base of the climb. Resolution Arete begins with a scary traverse across a cliff to a crack. Few people do the climb so there’s loose rock and difficult route finding. We ascended slower than anticipated.

The crux (or most challenging part) is a thin, overhanging finger crack about halfway up the 2,400-foot route. Imagine a small crack in the ceiling of the room you’re in right now. An exaggeration for sure, but that’s what it looked like to me from the hanging belay station below. It was this crux that would cause me so much grief.

GROWTH

Climbing is fundamentally about two things:

1. Personal growth

2. Connection

Italian climbing legend Walter Bonatti wrote that “climbing is not a battle with the elements, nor against the laws of gravity. It’s a battle against oneself.”

T.K. Coleman wrote that “the challenges you’ll have to overcome, the fears you’ll need to face, the mistakes you’ll make, the ecstatic moments you’ll experience, the people you’ll meet—these will all be triggers activating aspects of your soul that you never knew existed.”

These sentiments encapsulate my experience with Resolution Arete. As I hung from that rope high above the ground, I was terrified. I was physically and mentally exhausted. All I wanted to do was give up.

You know how sometimes you try really, really hard to do something, but you just can’t do it? What happens next? You typically have a couple options: You can give up, or you can give the task to someone else to do. But what if those options were taken away from you? What if your only option was to do it anyway? And what if your life—and your friend’s life—depends on you figuring it out?

That’s what I had to do on Resolution Arete. Jeff could yell advice to me, but ultimately, I had to make it happen. I had to calm my mind and focus completely on figuring out what to do. I had to find a way to get through the crux and keep climbing.

Since I was hanging away from the mountain, I knew that I had to ascend the rope. I needed to build a foot sling and connect it to the rope. But my hands were cold and I was shaking; I couldn’t do it right. I tried building the crude system but it kept failing. I would move up the rope a couple feet and then slide back down.

Austrian mountaineer Heinrich Harrer, author of Seven Years in Tibet, wrote that “you cannot completely summon all your strength, all your will, all your energy, for the last desperate move, until you are convinced the last bridge is down behind you and there is nowhere to go but on.” I knew there was nowhere to go but on. After some time I built the system and summoned the strength to climb up the rope. I placed my trembling right hand into a crack in the mountain and attempted to pull my body back onto the rock—and then I watched as my hand slowly slipped out. I fell back down again, dangling upside down in the open air.

Climbing forces you to accept reality. You must look objectively at your situation and deal with it. Each climb is like a puzzle, a challenge waiting for you to solve. In order to do it you must free your mind. You must overcome your fear of falling, your fear of failing, your fear of the unknown. You must ignore the past and the future, and focus your mind completely on the present moment—a moving meditation. You develop an understanding with yourself and the world around you, a peace in that moment. You are Zen. And in this process of being, you overcome. Your confidence, courage, and self worth grow.

Jeff learned to climb in Japan. One of his mentors was a young Japanese guy, a local legend that climbed harder and better than anyone else. Jeff asked his mentor for advice on how to improve as a climber. This was before the days of climbing gyms, so Jeff figured he’d suggest some outdoor training regimen. But instead his mentor said this: men-ta-ru toh-ray-neen-gu. Mental training. Free your mind. Focus. Visualize the climb. He taught Jeff that you can build your climbing skill anywhere simply by disciplining your mind.

Climbing makes you mentally strong. Once you push yourself to your limit on the rock, problems you face back on the ground seem small in comparison. The rest of life’s challenges become less daunting. The discipline that you cultivate applies to other aspects of your life: your career, your relationships, your desires.

And when you have that battle against yourself, when you are forced to dig deep and do something that seems impossible—something you just can’t do yet have no other option but do it—once you figure it out, you have an epiphany. Your mind expands. You grow.

Climbing makes you physically strong. Your entire body, muscles and ligaments from head to toe, get worked in a way that is impossible to achieve lifting weights in a gym. Perhaps more important, climbing inspires you to keep your body fit. Without climbing, I would lack the motivation to push myself to stay in the shape I do.

Not every climb pushes you to your limit. You don’t have to experience Resolution Arete to understand the essence of climbing. At its heart, climbing is fun. It’s going to the climbing gym and playing. It’s going outside and playing. What better way is there for an adult to experience the magical, carefree joy from childhood than taking a few days off work and playing outside with friends? The British mountaineer George Mallory explained this well when he wrote, “What we get from this adventure is just sheer joy.”

The most famous climbing book is called The Freedom of the Hills. Being in the mountains, unplugged from electronics and your typical daily stresses, makes you feel freedom and joy in a way that’s hard to capture elsewhere. But there’s a more important freedom that climbing provides. The Atlantic recently published a feature about an epidemic facing our country: college students graduating without a sense of autonomy—lacking self-worth, direction, and an ability to succeed in the world. Their ‘helicopter’ parents hover over and baby them, depriving them of their freedom to fully develop. Climbing has the opposite effect; being empowered to overcome obstacles fosters self-discovery.

Climbing gives you the freedom to grow.

CONNECTION

Climbing is about connection.

Sure you are physically connected to your partner through a rope, but that’s not what I’m talking about. Have you ever truly placed your life in someone else’s hands? Has anyone ever trusted their life completely in yours? Trusting your life to another, and having them trust their life with you, changes you. And it changes your relationship with your partners. It’s the kind of connection that only comes when you face death. Life becomes poignant.

Have you ever stood on top of a narrow mountain peak—one accessible only by scaling its steep cliffs—alongside a handful of friends, staring together at the horizon stretching all around?

This experience is profound.

Imagine that you and I just scaled the sheer walls of Oregon’s infamous Monkey Face. We are standing on the summit, just us and a few other climbing friends alone on top.

Imagine being there with Scott, Jeff, Isaac and me. Imagine watching the sunset together, as we did, and then rappelling back to the ground in complete darkness. Think about how that entire experience would feel. Imagine the connection you and I would share during those moments—and after.

I was talking with a good friend of mine, Price. He hit me up on gchat about a book he’s reading. Just a casual conversation, the way friends do. I tried to convince him to join us on an upcoming adventure. I met Price on a climbing trip in Red Rock Canyon. We got together again to scale the South Six Shooter (it looks just like it sounds) and the Castleton Tower in Utah. I just checked my climbing log: it’s been several years since I’ve seen Price. And, as I type this, I’m realizing that Price and I have only seen each other twice in our entire lives. That shocks me—I can’t believe I’ve only done two trips with him, and I can’t believe it’s been years since we’ve hung out—because he’s a close friend. Once you share an experience like the Castleton Tower with someone, your connection stays deep.

I’ll never forget that Utah adventure with Price. For several nights we sat around the same campfire, yet—like Heraclitus’ river—each night we had a different gathering of people: from doctors and lawyers to vagabonds. Climbers from around the planet connected for a moment through our mutual desire to experience the freedom of the hills. We would share stories and contemplate—as Conrad Gessner did five centuries ago—how the rock draws you in, breaks you down, builds you back up, and fills you with joy.

The climbing culture is built upon a mentorship connection. And as Jeff has mentored me, I have mentored others.

I took my friend Pericles climbing a few years back. It was his first multi-pitch adventure. We made it to the summit at sunset. As we worked our way to the rappel station to descend, we figured no other parties were on the mountain. The official season was over, so the climbing schools were closed and no one was around for help. If we got in trouble, we’d have to rescue ourselves. Halfway through my descent, I noticed the faint light from two headlamps penetrating the darkness below me. Two climbers were stuck and in trouble. The temperature was near freezing. One of the climbers was almost hysterical. They had a third member in their party up on the summit. But they were too far away to communicate. Pericles, who had not yet begun rappelling, was high enough up that he could shout to their friend. And we had two-way radios with us, so through Pericles and me the troubled team was back in contact. Working together, we got all three climbers onto my ropes and down the mountain safely. Less than six months later, Pericles returned to that same mountain as a knowledgeable climber, and safely led a team to the summit and back down to the ground.

Climbing is sublime. Not only do you connect deeply with your partners, you build a mystical connection with the natural world. There’s a French painting of a man all alone staring at a mountain sunset. The caption reads: “How beautiful this would be if only I could share it with someone.” In climbing, you have this experience all the time, except you always get to share it with someone. In fact, it goes beyond this, as you enjoy breathtaking works of nature inaccessible to non-climbers. You see the world from a unique vantage point.

Psychologist Jon Haidt explains in his fantastic book The Happiness Hypothesis that happiness requires not just personal growth, but also deep connections and relationships. As he puts it, happiness comes from between. We must build meaningful connections with other people, as well as with the world around us.

When I read Haidt’s insights into how to lead a happy, meaningful life, I feel like he’s describing climbing.

RISK

Of course, climbing is not for everybody. Some people are committed to staying indoors with their feet planted firmly on the ground. Others would rather not push themselves to their physical and mental limit. And many simply don’t want to take the risk, which is inherent in the vertical world.

H.L. Mencken, the Sage of Baltimore, wrote: “They have an unsurpassed view of the scenery, but there is always the possibility that it may collide with them.” He was describing hot air balloonists, but climbers apply just the same.

One time I was with Scott and Jeff on an alpine mountain called Matthes Crest when a guy climbed passed us, alone and unroped. We exchanged brief salutations and he was on his way. We’d find out later that his name was Brad Parker. He had just proposed to his girlfriend on a nearby mountain peak. She said yes. He called his father to share the good news and say that it was the happiest day of his life. Tragically, it was also his last. Shortly after passing us he slipped. Being unroped, he fell to his death.

If you decide to climb, you must understand the risks you are undertaking. George Mallory, who I quoted above, died young while attempting to summit Mount Everest. His body wasn’t discovered for 75 years. Every season from his disappearance to today there have been climbing fatalities. All are tragic. But almost all are preventable. You can mitigate the vast majority of your risk by using common-sense safety measures, understanding and applying proper techniques, and knowing your limit.

Wisdom comes from experience. There are several things I have learned during my time on the rock, numerous ways to avoid challenging situations I have created. Wisdom I apply today.

RESOLUTION

Eventually I got through the crux on Resolution Arete. Unfortunately, the next pitch wasn’t much better. It is also technically difficult, and I was too blown out mentally and physically to climb it well. I struggled. We realized that it would be impossible to complete the entire route that day, so we’d have to find a place to sleep on the rock for the night.

We each brought a space blanket. You always have one in your pack when you climb outside, though you never plan to use it. We found a small ledge, connected ourselves to the wall, and did our best to lie down. The ledge isn’t big enough to stretch out, so we curled up. When the sun went down, it got windy and cold. Very cold. Jeff’s blanket tore apart as he moved around for warmth. We shivered and stared down at the lights of the Vegas strip in the distance—such a contrast in conditions! We spoke and laughed thinking about how different the extravagant Dionysian exploits happening under those lights were compared to our situation. We did not sleep so much as endure the darkness until the sun rose.

We packed plenty of water for one day, but not enough for two. Several hundred feet of climbing into the second day we ran out of water. We were dehydrated. Our lips cracked to the point that they bled. Thankfully, the upper portion of Resolution Arete had snow. We packed it into our water bottles and sipped it as it melted.

We made it to the summit. But as the cliché goes, when you get to the top you’re only halfway there. Resolution Arete does not have a descent path. And the directions are vague at best. We bushwhacked and down climbed, unsure if we were going the right way. We came to a waterfall with a rappel rope. We backed it up with our gear and descended. Beneath the falls we built another rappel station with our own gear (leaving it behind) and descended further. As the sun set on the second day, we made it to the wash. We raced across the boulders as fast as we could, our climbing gear clanging, Jeff holding up my cell phone desperate to get a signal. When it came, he immediately called his wife. She was deeply relieved to hear his voice. She said the rescue helicopter was minutes from departure.

Inside the car, free at last from our harnesses and gear, completely exhausted, dehydrated, and bleeding from our cracked lips, Jeff turned to me and said, “well I don’t even know what to say about that.” We drove to Las Vegas in silence.

There’s an old mountaineer saying,“When you climb a mountain, you bring part of it back with you.” Jeff and I will always carry Resolution Arete with us. It forged who we are today.

CLIMB ON

It’s been more than a decade since that epic event. Time moves on. I’ve since left IJ and started my own company. Jeff started a family and moved to Texas. Scott is getting married and Isaac just had a baby. Maryrose and I left DC and live in a bus. There is plague everywhere. But, thanks to climbing, none of that holds us back. We still get together to unplug and play outside. As I type this, Maryrose and I are heading out in a few days to meet Jeff in Joshua Tree, one of the world’s premier climbing destinations.

Climbing to the top of a mountain with a close friend, placing your lives in each other’s hands, is an experience unlike any other. What better way is there to feed the wanderlust and commitment to adventure embedded in our being—that inescapable yearning to behold the world that lies within each of us? Italian poet Francesco Petrarca wrote that while standing on top of Mount Ventoux in France,“I was so affected by the unaccustomed spirit of the air, and by the free prospect, that I stood as one, stupefied.”

I can’t predict the future, but I can say this: I will climb for the rest of my life. I will stand stupefied on mountaintops on every continent. I will share these experiences with some of my dearest family and friends. They will be among the most intimate and meaningful moments of my life.

There are countless mountain summits out there waiting for us. Beckoning. Luring. I’ve had the fortune to tick off a few celebrated ones already: Australia’s Mount Arapiles, Carolina’s Stone Mountain, Oregon’s Monkey Face, Tuolumne’s Matthes Crest, Utah’s Castleton Tower, West Virginia’s Seneca Rocks, Yosemite’s Half Dome.

Nevada’s Mount Wilson.

Everyone has different goals in life. The same is true with climbing. Many climbers are content doing all their playing in a gym. Some are satisfied with nothing more than an occasional outing to a local park. And some of the best climbs in the world are not difficult. In two weeks Jeff and I will take our friend Renee up a scrambling romp called the Regular Route on Sunnyside Bench that tops out at the Lower Yosemite Falls swimming hole. You can do this wonderful climb—and when you get to the top you’ll be rewarded with an incredible view while swimming right in the middle of one of the tallest waterfalls in North America: It’s among the most magical and cathartic experiences imaginable.

That’s the beauty. Climbing is what you choose to make it. Regardless of your level of commitment, if you choose to climb, I promise you two things will happen: you will grow as an individual, strengthening your mind and body while discovering more about yourself; and you will build meaningful connections. Climbing is, paradoxically, an expression of both individuality and connection.

I all but assure you that your happiness and fulfillment will increase.

One example of the unique ego boost climbing gives you: Jeff and I summited Half Dome recently. There were more than a hundred tourists on top, having ascended via an arduous hike that culminates in the famous and scary metal cables. It’s likely the hardest thing many of them had ever done. When those tourists, standing proud upon that fabled peak, see you appear covered in climbing gear, they stare at you, dumbfounded. They ask you about climbing. They ask to take a picture with you. We had a strikingly beautiful woman walk away from two tall, shirtless, rippling studs to get her picture taken and hang out with us.

That makes you feel like a superhero.

You may find that just a little climbing will suffice. Or you may get full on addicted. Yosemite climbing legend Chuck Pratt wrote, “I cannot imagine a sport other than climbing which offers such a complete and fulfilling expression of individuality. And I will not give it up nor even slow down, not for man, woman, nor wife, nor God.”

The greatest climb in the world ascends the greatest rock formation in America. The place is Yosemite. The rock is El Capitan. The route is The Nose. Every climber’s dream is to climb it, yet few do. It doesn’t demand a perfectly sculpted body, or a brilliant mind, or Bobby Fischer’s work ethic. It simply requires training and determination.

One day, I will climb The Nose. Jeff agreed to do it with me. We’re on a multi-year training plan. We’ll climb the route in three days. At some point afterwards, I may climb it with Maryrose or Scott. And after that, perhaps I’ll ascend The Nose with Isaac, Pericles, Roger, Price, and others in my life that are important to me and willing to make the trek. Perhaps I’ll climb it with my grandkids. Perhaps I’ll climb it with you. The memories will be unforgettable. The stories we create during these adventures will last for the rest of our lives and, in a deeper sense, make us who we are.

Perhaps more important than The Nose, Jeff and I will return to Mount Wilson. We will bring with us an extra couple decades of experience and wisdom. And we will crush Resolution Arete and summit Mount Wilson in victory.

We will conquer the mountain that once almost conquered us.

I mean, why not?

***

An earlier version of this essay was published in the book, Why Haven’t You Read This Book?