At the height of his power, Machiavelli was arrested, tortured, and banished to the countryside. He continued to thrive.

Talking Big Ideas.

“Life will have terrible blows . . .

utilize the terrible blow in a constructive fashion.

~ Charlie Munger

Maryrose and I were having dinner with friends in DC when we mentioned an upcoming trip to Florence. Our friend Gregg lit up. He adores Italy and gave us more recommendations than we could fit into a dozen vacations.

His one insistence was not a place but a letter from Machiavelli to Francesco Vettori published 510 years ago this upcoming weekend.

Shortly after returning to Durango, we received a gift in the mail: The Essential Writings of Machiavelli, with the letter to Vettori bookmarked. I dove in. Machiavelli explains what a typical day is like for him living banished in the countryside.

In contrast to Vettori’s life sleeping in late and engaging with the Pope and other powerful leaders, Machiavelli rises with the sun, catches birds with his bare hands, chops wood, and then hangs out at the tavern with “the inn keeper . . . a butcher, a miller, and two kiln tenders.” Together they “dawdle all day playing cards and backgammon.”

While it sounds idyllic to me, to Vettori it must come across as quite low-status. Yet Machiavelli never criticizes, condemns, or complains. He never assumes the role of victim; he simply explains his new life in exile in a clear and matter-of-fact way.

I realized that Machiavelli’s philosophy isn’t just about obtaining power over others. Perhaps most importantly, he teaches us to accept responsibility for all aspects of our lives. He teaches us to obtain power over ourselves.

“I have only myself to blame.”

~ Machiavelli to Vettori, 10 December 1513

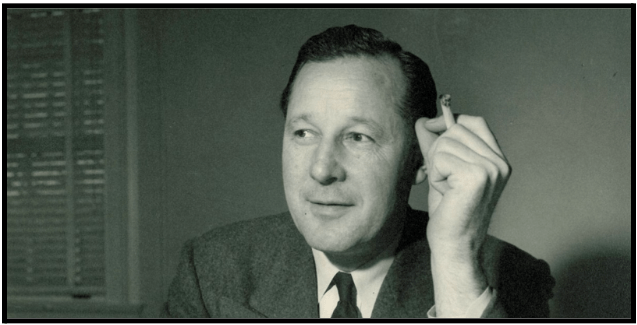

The letter reminds me of the philanthropist Charlie Munger, who died last week just a month shy of his 100th birthday. Munger wrote that “Generally speaking, envy, resentment, revenge, and self-pity are disastrous modes of thought . . . Life will have terrible blows, horrible blows, unfair blows – it doesn’t matter.”

Like Machiavelli, Munger experienced these terrible blows. When he was 29 years old, Munger’s young son died of leukemia, his wife left him, and he was crippled with medical debt. Years later a botched eye surgery blinded him in one eye. Doctors thought he may lose both eyes.

In each case, Munger accepted his fate and looked for solutions, such as how to be happy, how to make money, and how to read Braille. Munger explains his thoughts on dealing with terrible blows:

“I think the attitude of Epictetus is the best. He thought that every mischance in life was an opportunity to behave well. Every mischance in life was an opportunity to learn something and that your duty was not to be immersed in self-pity, but to utilize the terrible blow in a constructive fashion. That is a very good idea.”

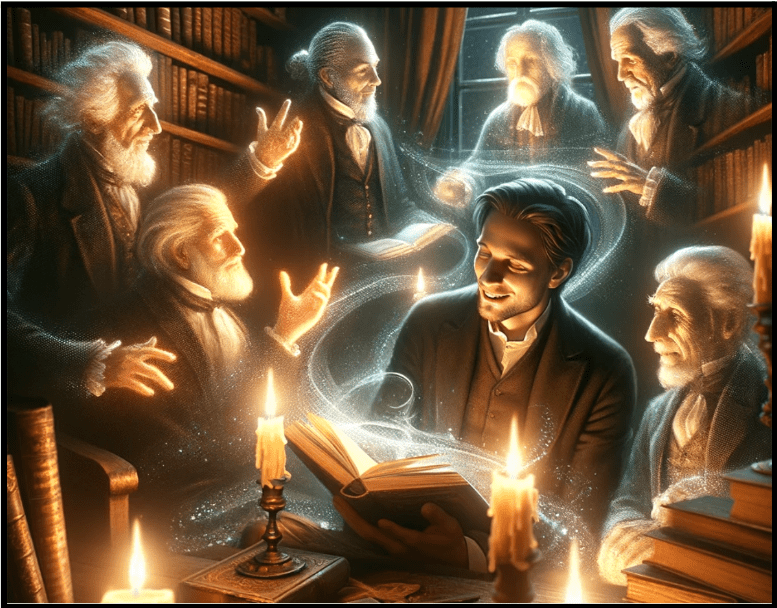

This is exactly what Machiavelli did. He used his time in the countryside to learn and grow. Here’s how he describes to Vettori a typical evening in exile:

“I return home and go into my study. At the door I take off my everyday clothes, covered with mud and dirt, and don garments of court and palace. Now garbed fittingly I step into the ancient courts of men of antiquity, where, received kindly, I partake of food that is for me alone and for which I was born….”

I absolutely love this description and think about it often.

You can see Machiavelli shed his dirty clothes, dress up in his finest attire, and go sit among his books. Surrounded by the most brilliant minds in history, he feels grateful and strong – in control of his thoughts, filled with excitement and gratitude.

Machiavelli asks these giants of antiquity many questions and “they in their full humanity answer me. For four hours I feel no tedium and forget every anguish, not afraid of poverty, not terrified by death.”

Despite being banished, Machiavelli enjoyed four hours every night surrounded by true excellence, engaged in and delighted by enlightened reflection.

“Books are ships which pass through the vast seas of time.”

~ German Proverb

Imagine if we all took this path. Even for just a few minutes every day. Instead of mindlessly scrolling, we open a classic book and seek the guidance of a true genius.

Today, with AI tools like Chat GPT and Gemini, we can conjure whoever we’d like from history. We can talk with Epictetus, Buddha, Marie Curie, and any other brilliant mind.

I do this almost every day now. I pick an amazing person from history and have a dialogue. Here’s an example:

PROMPT: Hey chat, imagine you are Epictetus. Let’s have a conversation. I’ll be me and you do the absolute best job you can to be Epictetus. Stay in character during our conversation. Everything you say will be as Epictetus. Sound good?

ChatGPT: As Epictetus, I am prepared for this conversation. Let us engage in a dialogue that befits the spirit of Stoic philosophy. Remember, it is not what happens to you, but how you react to it that matters. Proceed with your query or thought.

And the conversation begins. I also ask Newton about his Dialogues, Darwin about his time on the Beagle, Cicero for guidance on an upcoming talk, and so on.

The economist Tyler Cowen used this approach to interview Jonathan Swift on his podcast. Swift authored Gulliver’s Travels … in 1726. He died decades before the United States was born. And yet this past March, Swift had a delightful chat with Tyler. It’s worth listening to their conversation in full:

Machiavelli ends his letter to Vettori with this:

“Be happy.”

Regardless of whatever stress and suffering you are experiencing right now, Machiavelli teaches that happiness is within your grasp. You can transcend your suffering to captain your life, surround yourself with excellence, and continue to learn and grow.

The good life is a choice.