Talking Big Ideas.

“The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones.”

~ John Maynard Keynes

Thousands of years ago, Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, proposed a radical idea: wealth should be shared, and the needs of all citizens should be met.

The first Christians lived this idea, and Islam passed laws to give generous stipends to the poor. Philosophers kept the dream alive for millennia, and economists would later join them in calling for a Universal Basic Income (UBI), from socialists like Joseph Charlier to classical liberal Nobel laureates Friedrich Hayek and James Buchanan.

Even Milton Friedman agreed, proposing a Negative Income Tax where the rich pay taxes and the poor get free money.

Enter Rutger Bregman.

The precocious Dutch historian was in his mid-20s when he published Utopia for Realists, a global blockbuster that took up the mantle to argue for UBI, concluding: “Studies from all over the world offer proof positive: Free money works.”

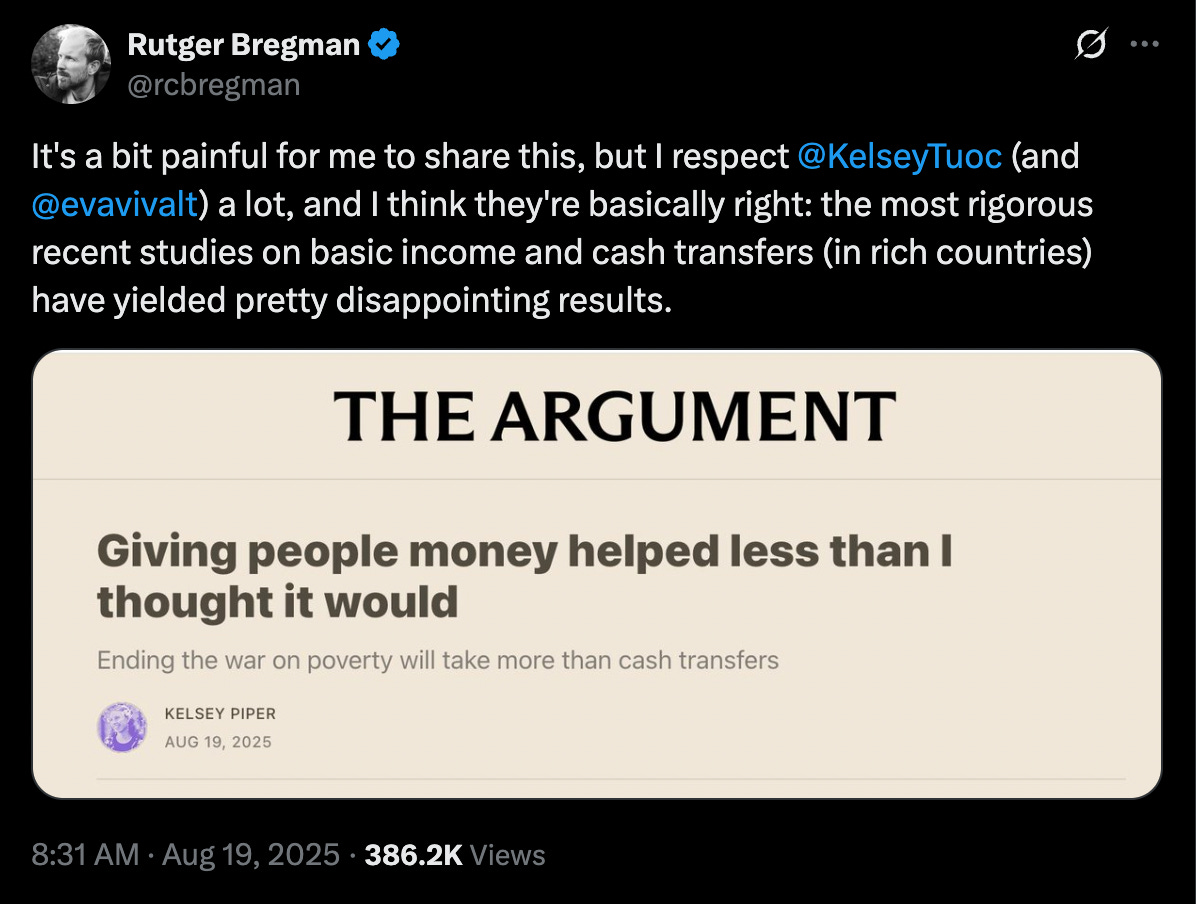

For his entire adult life, Bregman has fought passionately for this cause. And then on August 19th, he tweeted this:

I was shocked to read it, as Bregman is the Patron Saint of the cause!

Importantly, he clarified that while UBI struggles in rich countries, it does very well in poor countries. And has since added more nuance.

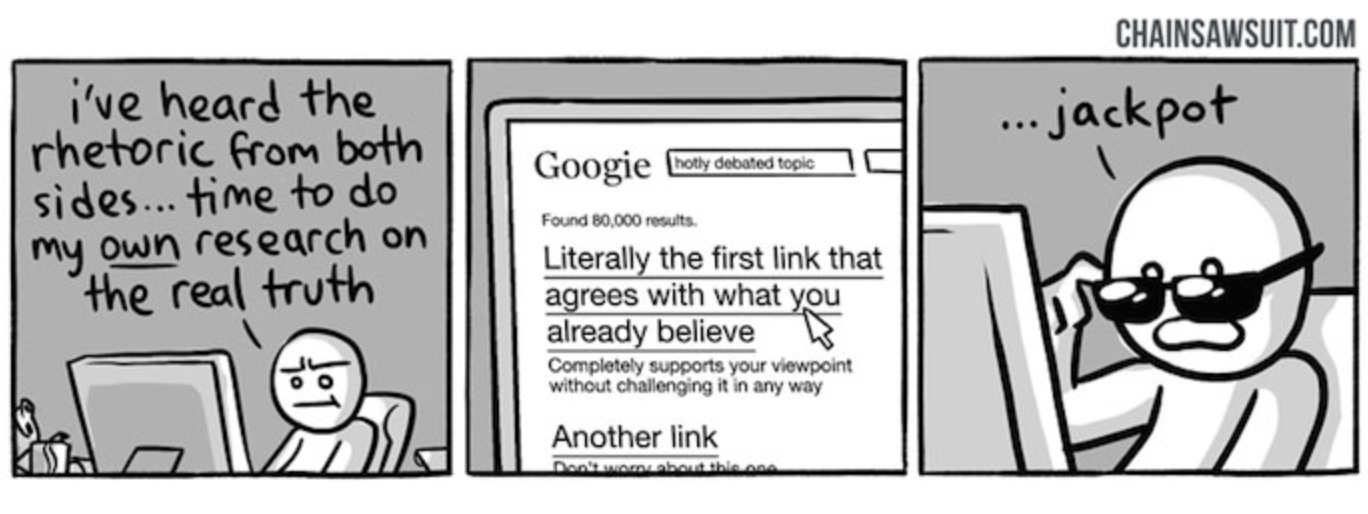

On the one hand, the tweet is disappointing because I want UBI to work. But, in a larger sense, I love it because it embodies the ideal approach to seeking truth. The philosopher John Stuart Mill explained in his masterpiece On Liberty that when you encounter opposing ideas, three possibilities should be kept in mind:

- You may be wrong. Regardless of how certain you feel.

- Conflicting opinions often share the truth. Rarely is one side wholly right and the other wholly wrong, especially on moral and political questions.

- Even if virtually everyone thinks your position is correct, engage honestly with the criticism. If only to sharpen your own mind. As Mill famously wrote, “he who knows only his side of the case knows little of that.”

The American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce built on Mill’s foundation to become the Father of Fallibilism, teaching that we must always be open to being wrong, that all our knowledge is provisional, and that progress comes through engaging with people and their differing ideas.

Fallibilism means that no matter how much we know, no matter how impressive our learning, credentials, or achievements, we may still be mistaken. From this humility rises tremendous potential and optimism: because error correction can continue forever, our knowledge and capabilities can grow without limit.

By embracing fallibilism not just as individuals but as a species, the physicist David Deutsch says we can stand always at the beginning of infinity, on the threshold of fantastical futures bound by nothing but the laws of physics.

Stephen Hawking argued for 30 years that nothing can escape black holes. When he was presented with good evidence that he was wrong, Hawking publicly changed his mind and declared his critics correct. Einstein did the same.

Greg Lukianoff, the president of FIRE, introduced me to the Polish poet Wisława Szymborska, who said in her 1996 Nobel Prize acceptance speech: “Whatever inspiration is, it’s born from a continuous ‘I don’t know.’”

How refreshing and admirable!

My friend Nathan is quite good at applying this “epistemic humility” in philosophic conversations, quick to admit he may not be correct, and presenting positions different from his own. My default, by contrast, is to get super excited about things and risk being blind to their flaws.

Consider how our ancestors thought.

The publication of one popular book on witchcraft in the Middle Ages created a frenzy that led to the persecution and death of thousands, and perhaps even a million, innocent people feared to be witches. David Wootten writes in The Invention of Science about a typical educated English person from the early 1600s:

He believes he can summon up storms that sink ships at sea . . . He believes in werewolves . . . He believes mice are spontaneously generated in piles of straw . . . He believes that comets portend evil . . . that dreams predict the future . . . that the earth stands still and the sun and stars turn around the earth.

Imagine if we still thought this way – what a poorer world we would have! Thankfully, we’ve grown as a people by changing our minds.

Adjusting course based on new information is the path to progress in our universe, from engineering to biology to skill development and ideas: the more we embrace feedback and iterate, the more we make progress and grow.

We can choose to channel our inner fallibilist and be like many of the most admirable philosophers and scientists. As the Pulitzer-winning author Kathryn Schulz writes in her book Being Wrong:

[W]e are wrong about what it means to be wrong. Far from being a sign of intellectual inferiority, the capacity to err is crucial to human cognition. . . . wrongness is a vital part of how we learn and change. Thanks to error, we can revise our understanding of ourselves and amend our ideas about the world.

At the end of his latest international bestseller, Moral Ambition, Rutger Bregman quotes Nelson Mandela: “One of the most difficult things is not to change society, but to change yourself.”

Big cheers to Bregman for being open to doing exactly that.