Talking Big Ideas.

“Thermonuclear war… would mean devastation on a scale that no preceding age could conceive.”

~ Herman Kahn, On Thermonuclear War

A haunting sentence opens Daniel Ellsberg’s final book, The Doomsday Machine:

One day in the spring of 1961, soon after my thirtieth birthday, I was shown how the world would end.

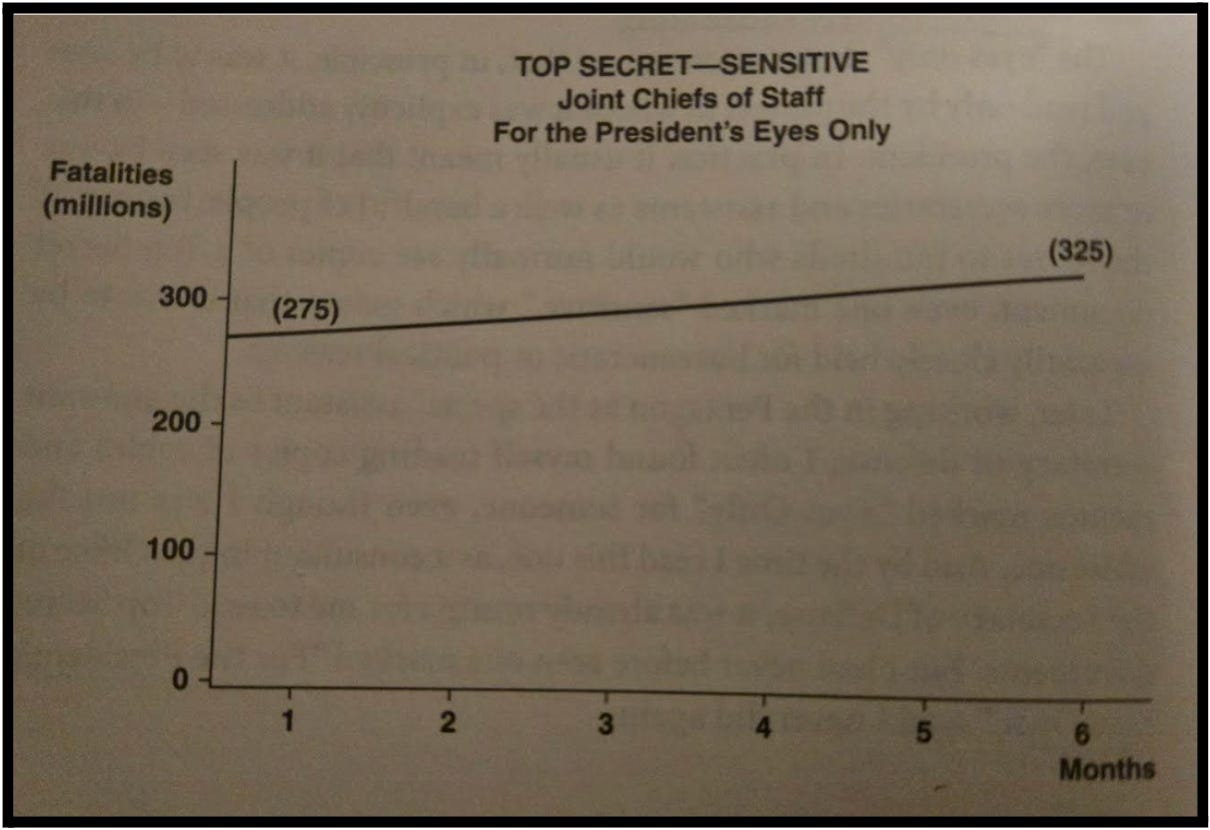

Ellsberg – who worked for the Department of Defense and famously drafted Robert McNamara’s plans for nuclear war (and then infamously leaked the Pentagon Papers) –explains how he was standing in the Oval Office when his boss showed him “a single piece of paper with a simple graph on it” marked For the President’s Eyes Only.

The graph showed how many people would be killed in the Soviet Union and China if the United States carried out its plans for nuclear war. It looked like this:

275 million people would die immediately. Another 50 million would join them in the coming months from injuries and radiation exposure.

And the graph didn’t show all the other countries that would be affected. The Joint Chiefs predicted another 100 million dead from fallout in Eastern Europe, perhaps another hundred million more in Western Europe “depending on which way the wind blew,” and then another hundred million in nearby neutral countries like Afghanistan, Finland, India, Japan, and Sweden.

In total, about 600 million dead.

As Ellsberg put it: “A hundred Holocausts.” And if the Soviet Union also carried out its nuclear war plan, the human toll would likely have soared well past a billion, resulting in the near-certain destruction of civilization.

The Soviet leader Khrushchev wasn’t lying when he said, “In the event of a nuclear war, the living would envy the dead,” which makes his iconic threat to the United States – “We will bury you!” – all the more frightening.

Einstein was prescient in lamenting that “we drift toward unparalleled catastrophe.”

And yet, the Cold War ended peacefully.

This is an astonishing truth. It must have seemed inconceivable for decades, given the constant threat of annihilation between the two ideologically opposed superpowers.

I think about this when I hear people say we’ve never been more divided today. Or that the future is bleak. There’s no chance for common understanding, no hope for bridging our divides or building a better world.

Nonsense.

We absolutely can heal our divisions and come together to make progress, just as General Secretary Gorbachev and President Reagan did. The key is dialogue.

Gorbachev was a dedicated communist; Reagan a staunch capitalist. They were pitted against each other, destined to be mortal enemies, inheriting a Cold War itching to turn hot and set the world ablaze.

Instead, they became friends.

They were known for their honest conversations with each other, working to see the world through each other’s eyes. Their dialogue slowly reduced tension, built trust, and ultimately paved the way for cooperation and understanding.

One January day in 1988, less than three decades after Khrushchev delivered his We Will Bury You! speech, Gorbachev delivered his own historic speech to the United States – in the United States!

He highlighted milestone successes from the previous year, painted a shared vision for the future, and wished “peace, happiness, and joy to every American family.”

On the same day, President Reagan delivered a speech to the Soviet Union, from the Soviet Union, concluding with an optimistic call for courage:

There is no such thing as inevitability in history. We can choose to make the world safer and freer if we have courage — but then courage is something neither of our peoples have ever lacked. . . . Let us consecrate this year to showing not courage for war but courage for peace. We owe this to mankind. We owe it to our children and their children and generations to come.

These January speeches would have been unthinkable in 1961 when Ellsberg was shown the graph on nuclear casualties. Dialogue made them possible.

Far from mere ceremonial formalities, these speeches helped shape the public narrative and transform U.S.-Soviet relations during a critical moment in world history.

As we begin 2025 – transitioning to a new presidential administration amid stark ideological differences – I encourage you to take inspiration from Gorbachev and Reagan. To summon the courage to rise above default tribalism and resist the desire to criticize, express outrage, or feel hopeless.

I challenge you to reach across ideological divides, to learn from and come to truly understand those who think differently than you – and begin by taking a moment to read Gorbachev’s and Reagan’s speeches in full. They are short and republished below.

***

Gorbachev’s Speech to the United States

Ladies and gentlemen, friends, as we celebrate the New Year, I am glad to address the citizens of the United States of America and to convey to you season’s greetings and best wishes from all Soviet people.

The first of January is a day when we take stock of the past year and try to look ahead into the coming year. The past year, 1987, ended with an event which can be regarded as a good omen. In Washington, President Reagan and I signed a treaty on the elimination of intermediate and shorter range missiles. That treaty marks the first step along the path of reducing nuclear arms, and that is its enduring value. But the treaty also has another merit: It has brought our two peoples closer together. We are entering the New Year with a hope for continued progress, progress towards a safer world.

We are ready to continue, fruitfully, the negotiations on reducing strategic arms with a view to signing a treaty to that effect even in the first half of this year. We would like, without delay, to address the problem of cutting back drastically conventional forces and arms in Europe. We are ready for interaction in resolving other problems, including regional ones.

I think it can be said that one of the features of the past year was the growing mutual interest our two peoples took in each other. Contacts between Soviet and American young people, war veterans, scientists, teachers, astronauts, businessmen, and cultural leaders have expanded greatly. Like thousands of strands, those contacts are beginning to weave into what I would call a tangible fabric of trust and growing mutual understanding. It is the duty of Soviet and American political leaders to keep in mind the sentiment of the people in their countries and to reflect their will in political decisions.

The Soviet people are getting down to work in the New Year with an awareness of their great responsibility for the present and for the future. There will be profound changes in our country along the lines of continued perestroika, democratization, and radical economic reform. In the final analysis, all this will let us move on to a broad avenue of accelerated development.

We know that you Americans have quite a few problems, too. In grappling with those problems, however, I feel that both you and we must remember what is truly crucial: Human life is equally priceless, whether in the Soviet Union, the United States, or in any other country. So, let us spare no effort to affirm peace on Earth.

Ladies and gentlemen, during the official departure ceremony in Washington, I said with regret that on that visit I had had little chance to see America. I feel, however, that I did understand what is most important about the American people, and that is their enormous stock of good will. Let me assure you that Soviet people, too, have an equally great stock of good will. Putting it to full use is the most noble and responsible task of government and political leaders in our two countries. If they could only do that, what is but a dream today would come true: a lasting peace; an end to the arms race; wider ranging trade; cooperation in combating hunger, disease, and environmental problems; and progress in ensuring human rights and resolving other humanitarian issues. May the coming year of 1988 become an important milestone as we move down that road.

In concluding this New Year address to the people of the United States of America, I wish peace, happiness, and joy to every American family. A happy New Year to all of you.

***

Reagan’s Speech to the Soviet Union

Good evening. This is Ronald Reagan, President of the United States. I’m speaking to you, the peoples of the Soviet Union, on the occasion of the New Year.

I know that in the Soviet Union, as it is all around the world, this is a season of hope and expectation, a time for family to gather, a time for prayer, a time to think about peace. That’s true in America, too. At this time of year, Americans travel across the country — in their cars, by train, or by airplane — to be together with their families. Many Americans, of course, came to the United States from other countries, and at this time of year, they look forward to hosting friends and family from their homelands.

Most of us celebrate Christmas or Hanukkah, and as part of those celebrations, we go to church or synagogue, then gather around the family dinner table. After giving thanks for our blessings, we share a traditional holiday meal of goose, turkey, or roast beef and exchange gifts. On New Year’s Eve we gather again, and like you, we raise our glasses in a toast to the year to come, to our hopes for ourselves, for our families, and yes, for our nation and the world.

This year, the future of the Nation and the world is particularly on our minds. We’re thinking of our nation, because in the year ahead, we Americans will choose our next President. Every adult citizen has a role to play in the making of this decision. We will listen to what the candidates say. We will debate their views and our own. And in November we will vote. I’ll still be President next January, but soon after that, the man or woman leading our country will be the one the American people pick this coming November.

As I said, we Americans will also be thinking about the future of the world this year — for the same reasons that you’ll be thinking of it, too. In a few months, General Secretary Gorbachev and I hope to meet once again, this time in Moscow. Last month in Washington, we signed the intermediate nuclear forces treaty, in which we agreed to eliminate an entire class of U.S. and Soviet nuclear weapons. It was a history-making step toward reducing the nuclear arms of both sides, but it was just a beginning.

Now in Geneva, Soviet and American representatives are discussing a 50-percent reduction in strategic nuclear weapons. Perhaps we can have a treaty ready to sign by our meeting in spring. The world prays that we will. We on the American side are determined to try. You see, we have a vision of a world safe from the threat of nuclear war, and, indeed, all war. Such a world will have far fewer missiles and other weapons. Today both America and the Soviet Union have an opportunity to develop a defensive shield against ballistic missiles — a defensive shield that will threaten no one. For the sake of a safer peace, I am committed to pursuing the possibility that technology offers.

The General Secretary and I also anticipate continuing our talks about other issues of deep concern to our peoples — for example, the expansion of contact between our peoples and more information flowing across our borders. Expanding contacts and information will require decisions about life at home that will have an impact on relations abroad.

This is also true in the area of human rights. As you know, we Americans are concerned about human rights, including freedoms of speech, press, worship, and travel. We will never forget that a wise man has said that: “Violence does not live alone and is not capable of living alone. It is necessarily interwoven with falsehood.” Silence is a form of falsehood. We will always speak out on behalf of human dignity.

We Americans are also concerned, as I know you are, about senseless conflicts in a number of regions. In some instances, regimes backed by foreign military power are oppressing their own peoples, giving rise to popular resistance and the spread of fighting beyond their borders. Too many mothers, including Soviet mothers, have wept over the graves of their fallen sons. True peace means not only preventing a big war but ending smaller ones, as well. This is why we support efforts to find just, negotiated solutions acceptable to the peoples who are suffering in regional wars.

There is no such thing as inevitability in history. We can choose to make the world safer and freer if we have courage — but then courage is something neither of our peoples have ever lacked. We have been allies in a terrible war, a war in which the Soviet peoples gave the ages an enduring testament to courage. Let us consecrate this year to showing not courage for war but courage for peace. We owe this to mankind. We owe it to our children and their children and generations to come.

Happy New Year! Thank you, and God bless you.