Talking Big Ideas.

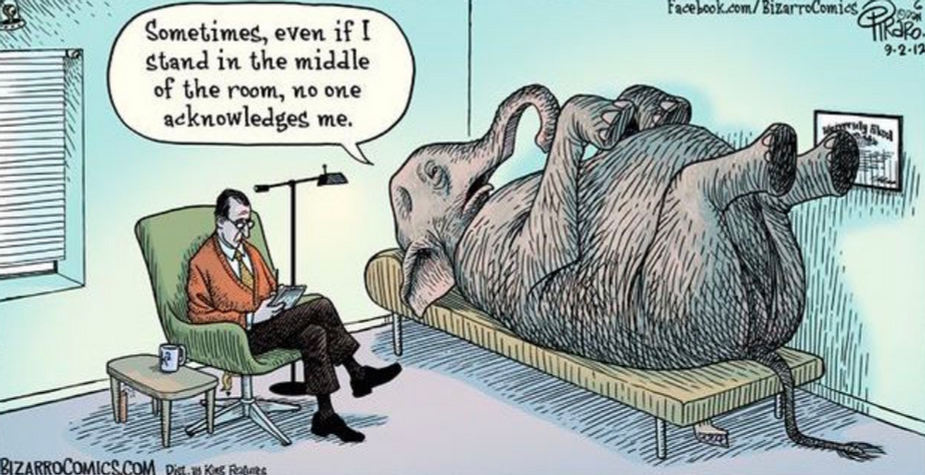

“What elephant??”

~ Jimmy Durante in Jumbo

The moment Ronald Reagan was inaugurated he became the oldest president ever.

So when he ran for re-election four years later, the public wondered if he would still be able to lead. He knew his age was a liability.

Walter Mondale, his opponent, was a distinguished and attractive former vice president. And nearly twenty years younger. In their first televised debate, Reagan appeared dazed and confused. Mondale was sharp and clear.

The Reagan-friendly Wall Street Journal ran a brutal front-page headline: Is Oldest U.S. President Now Showing His Age? Reagan Debate Performance Invites Open Speculation on His Ability to Serve.

Their second debate was two weeks later. Everyone knew Reagan’s age would be highlighted.

The moderator wasted no time: “You already are the oldest president in history. And some of your staff say you were tired after your most recent encounter with Mr. Mondale.” He went on to ask if Reagan was too old to continue in office.

The President responded with one of the most legendary lines in the history of American debate:

Not at all. . . . I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit for political purposes my opponent’s youth and inexperience.

The audience erupted in laughter. Mondale joined them – and admitted later he knew at that moment the election was over. The tension around Reagan’s age dissolved.

Two weeks later Reagan won re-election with 525 electoral votes, the most dominant victory in U.S. presidential history. As Mark Twain wrote, “against the assault of laughter, nothing can stand.”

My client Kaleb also has an age problem.

He’s a policy expert in Louisiana. He’s young. And looks even younger. People confuse him for an intern, a page, or even a high school student.

His youthful appearance is distracting. Many times he has presented at events and had audience members approach him afterward. But instead of asking him about policy, they ask about his age. So now he addresses his elephant before anyone else gets the chance.

A couple of weeks ago Kaleb presented to legislators on a panel with other policy experts. He was decades younger than the average person in the room. This is how he began:

You’re probably wondering why someone who looks like an 11th grader is here to lecture you about policy at eight o’clock in the morning.

Like Reagan, he got immediate laughter. Then everyone listened closely to the rest of his remarks. No one asked him afterward about his age or experience.

Harvard Business Review notes that humor “reduces hostility, deflects criticism, relieves tension, improves morale, and helps communicate difficult messages.”

Why is it so effective?

Sophie Scott may have the answer. She’s a cognitive neuroscientist and one of the world’s leading experts on humor. Her research suggests that the evolutionary purpose of laughter is to create social bonding.

When you laugh with someone, you immediately feel more connected to them. As the pianist Victor Borge said, “laughter is the shortest distance between two people.”

But humor is a double-edged sword. It can easily backfire and turn an audience against the speaker. One way to avoid this is to direct it at yourself.

After Al Gore lost a close and controversial presidential election, he would open his presentations by attacking . . . himself. Watch the opening to his 2006 TED talk.

Notice how quickly he sets the audience at ease by addressing his elephant. And how long he spends on it. For five minutes he tells increasingly self-deprecating stories. Importantly, he only makes fun of himself. And the audience loves it.

Humor isn’t necessary when addressing your elephant. If humor is unnatural for you, don’t force it. Awkward jokes that feel inauthentic can be cringe-inducing.

You can simply address your elephant in a direct way. In sales, this is called the power of pre-empting an objection.

The best example I’ve seen is the (explicit) climax of the movie 8 Mile.

Two musicians are on stage. Each gets a turn to rap. Their goal is to roast each other. The first rapper, played by Eminem, unexpectedly lists his own faults. So when the second rapper gets to go, he has nothing to say.

Eminem won the crowd by highlighting his most embarrassing qualities. But is that a good idea for professional speakers?

George W. Bush did exactly that when he was president. Everyone heard that he was stupid. Even though it wasn’t true, it was his brand. Rather than respond with anger, Bush would open speeches like this:

Before I left Texas, my wife Laura said to me, ‘Honey, don’t try to be charming. Don’t try to be witty. Don’t try to be eloquent. Just be yourself.’

***

![]() IDEA

IDEA

Own your elephant.

What is something about you or your message that could be potentially distracting? Consider how you can quickly acknowledge it in a humorous way.

BONUS: Listen to the opening minute of Ronald Reagan’s first State of the Union address. See if you can resist laughing.

***

At some point, you’ll find yourself listening to a speaker who doesn’t acknowledge their elephant. Do your best to stay focused on their message. Don’t pull an Austin Powers.

And for an example of humor backfiring, look no further than this weekend’s Oscars.

If you find this useful, please subscribe to our free weekly newsletter.