Talking Big Ideas.

“[T]hink first and speak afterward. If you . . . do that, you will not have any trouble.”

~Laura Ingalls Wilder

Roger Edgeworth was born in a castle.

Built along the River Dee after England invaded Wales in 1277, the five-towered fortress was home to a dozen generations by the time Roger arrived. He left in 1503 to study at Oxford.

Roger loved theology and gained a reputation as a devoted Roman Catholic and gifted orator. His speeches traveled far, across Europe and through the centuries.

In 1557, he published Sermons Very Fruitful, Godly and Learned. Still in print, it contains the first known reference to a classic proverb:

Think well and thou shalt speak well.

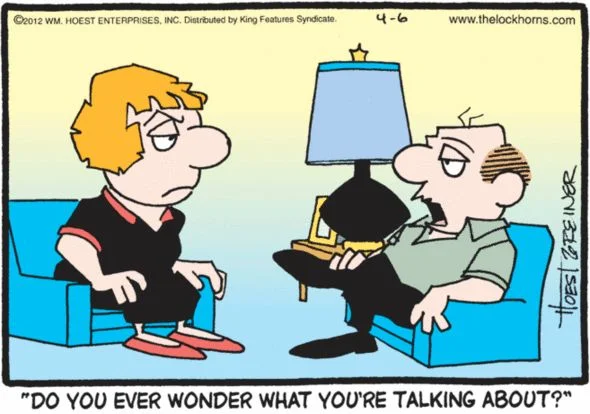

Think before you speak. This wisdom transcends time. Yet half a millennium later we see it violated everywhere. Talking heads blather. Celebrities mindlessly tweet. Politicians gaffe.

You and I ramble during conversations.

We all fail, at least occasionally, to think through our words in advance.

I’ve helped people improve their speaking skills for years. And I find that presenters often avoid practicing for as long as possible. And then focus most of their limited training on delivery: stage presence, vocal inflection, expressiveness, etc.

But before we can polish how we talk, we have to be clear about what we want to talk about.

Muddled messaging is distracting — for the listener as well as the speaker. Practicing for an upcoming talk without clear content inevitably results in stumbling, stopping, searching for words, frustration, and little progress.

To avoid the initial discomfort of thinking through content, countless presenters end up taking this futile approach.

It’s like training in hard mode.

As I sit at my computer now, a rug is being dropped off at our front door. Imagine the UPS driver deciding that he wants to get better at delivering packages. Surely with advice, practice, and feedback, he can make progress.

But what if he didn’t know what packages to deliver? How silly it would be for him to focus on his delivery skills if he had nothing to deliver!

The same applies to public speakers.

Messaging is foundational.

When preparing for an upcoming talk, start thinking early about what you want to say. Capture your ideas as they arise. Block off space on your calendar to read and think. If you’re truly limited on time, consider working with a speech writer.

What’s the big idea you want to make sure everyone understands? How can you bring it to life with stories, analogies, and vivid details? Sketch an outline that ties everything together.

This week I had two workshops at the Mercatus Center. I was inspired to see how much progress each speaker made in polishing their messaging after just a few minutes of collaboration with colleagues.

I encourage you to do the same. Test your messaging. Ask family, friends, and co-workers for feedback. Use their advice to tweak, edit, and polish.

Save what you build. Watch it grow over time.

Channeling Roger Edgeworth, the bestselling author Scott Berkun explains in Confessions of a Public Speaker:

All good public speaking is based on good private thinking. . . . Making a point, teaching a lesson, or conveying a feeling to others first requires thinking, lots and lots of thinking, before the speaking ever happens.

Build a habit of thinking through, capturing, and polishing your ideas on an ongoing basis. Your practice sessions for important presentations will be significantly easier and more productive.

Come game day, you’ll be ready to crush it.

***

![]() IDEA

IDEA

Think first. Speak later.

Imagine that I’ve just called you on the phone. And I ask you to give me a quick 30-second description of a project you’re working on. Without thinking, say it out loud right now.

When you’re done, take a few minutes and think about how you can best describe the project. What’s the problem you’re solving? What’s a compelling way to bring the project to life? After giving it thought, say your quick description out loud again.

Which version is better?

***

If you find this useful, please subscribe to our free weekly newsletter.