Talking Big Ideas.

“An overnight success is ten years in the making.”

~ Tom Clancy, Dead or Alive

This summer I was in a training session with a few executives.

They all had huge presentations coming up. More than a thousand people would be in the crowd to see them deliver their remarks. Towards the end of our session one executive said to another:

“Matt, you’re amazing at this. You’re just a natural.”

Afterwards Matt confided it was one of the best compliments he’s ever received. Years ago, he told me, he was pulled aside at work. The Board wanted to make him president of their organization. But there was one issue that had to be addressed.

“Matt, you need to get better at public speaking.”

Early on in Matt’s speaking career, he was asked to give a talk at a conference. It was in a huge auditorium with only a handful of attendees in the audience.

He was so nervous he stumbled and sweat profusely through the entire speech. It felt like everyone in the audience was cringing in embarrassment for him. The usher even offered Matt a towel after he finished his speech.

Public speaking, Matt assures me, did not come naturally for him.

Nor did it for Warren Buffett. Known today as an exceptional communicator, Buffett used to be so scared to speak that he avoided it at all costs. Sir Richard Branson, the suave billionaire innovator, had his mind go blank while he “mumbled incoherently” during an early attempt behind the lectern. “It was one of the most embarrassing moments of my life,” he says.

Joel Olsteen is a pastor with a massive following, largely attributed to his spellbinding sermons. He says it took a full ten years to build his craft. Stepping on stage for his first speech was terrifying.

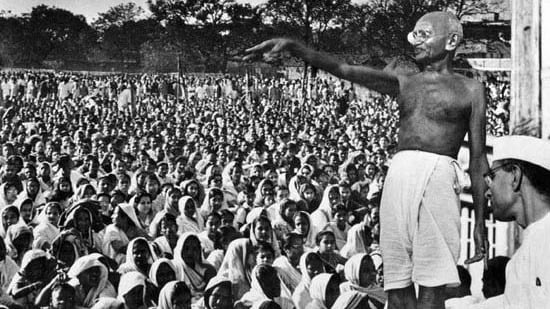

How about Gandhi, among the most influential speakers of the past century? When he first started presenting in public he would get panic attacks. One time he spoke just a single line before shutting down and forcing someone else to finish.

The truth is, the only thing “natural” about speaking in public is feeling awkward and uncomfortable. And while we all share this same initial fear, we do start with different baseline skills. But even high baselines are left in the dust by people who keep making progress.

This applies broadly in life.

You’ve probably heard that Michael Jordan was cut from his high school basketball team. He also wasn’t recruited to the college he loved. Nor was he drafted first in the NBA. This isn’t because the coaches and recruiters were dumb. It’s because Jordan didn’t start out as the best. He attributes his success, not to innate talent, but to mental toughness and hard work.

Wilma Rudolph was the fastest woman on earth after winning three gold medals at the Olympics. Yet she was born premature and left partially paralyzed by scarlet fever, double pneumonia, and polio. She wore leg braces throughout her childhood. Doctors said she would never walk normally. In her first track meet, she lost every race she ran.

Charles Darwin’s father was convinced his restless son would amount to nothing but embarrassment. Beethoven’s early teachers said he was hopeless. Elvis was rejected as the singer of a successful band. Stick to truck driving, he was told, because “you’re never going to make it as a singer.”

Everywhere you look for natural talent, the story is the same. Baselines are irrelevant. What matters is commitment to growth. This is the capital-T Truth about skill development:

Excellence isn’t natural. Excellence is built.

We build ourselves by being willing to block off time on our calendars, embrace whatever flaws we have, and practice. And then listen to feedback and practice some more.

The scientist Jill Bolte Taylor’s talk about her stroke went viral in 2008 and catapulted the TED conference into the global limelight. Why was she so successful? As she says:

“I practiced literally hundreds of hours.”

***

![]() IDEA

IDEA

Excellence isn’t natural. Excellence is built.

Who is someone you think of as a natural in their field? It can be for speaking, sports, or anything else. Spend a few minutes learning about their life. Ask yourself: how much effort went into them becoming a natural?

BONUS: Please share what you find with me!

***

Last month we discussed Garry Kasparov, the greatest chess player in history. In a recent tournament he set a new record — for the quickest loss by a former World Champion. He also won just one of his 18 games there. What happened? His answer was simple. He didn’t practice enough. Last week the world’s chess elite gathered for another tournament. Kasparov promised he would show up and do better. He’d practice hard this time. The result?

He crushed it! Beating many of today’s best players, he entered the finals with the chance to win the entire tournament. He ended up in fifth place, ahead of many luminaries.

When the media interviewed him this weekend, instead of having to explain a poor performance, he got to channel his inner Mark Twain: “The rumors of my chess death have been slightly exaggerated.”

***

If you find this useful, please subscribe to our free weekly newsletter.