Talking Big Ideas.

“A weasel . . . sucks the meat out of the egg and leaves it an empty shell.”

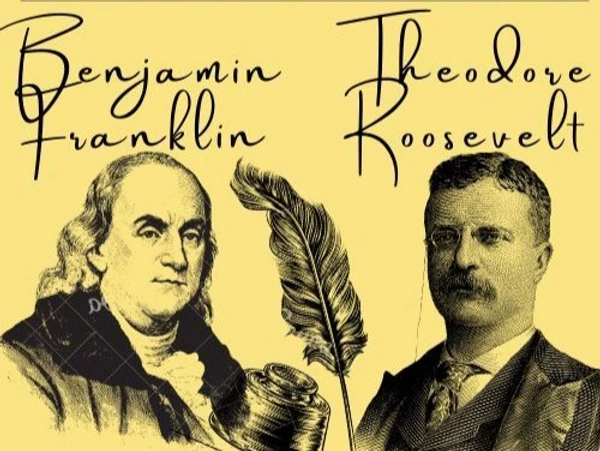

~ Teddy Roosevelt

A few weeks ago we discussed one of the most common problems in speaking: filler words. They have a close cousin: qualifiers.

Qualifiers are words and phrases that soften the impact of our message. Perhaps you could consider. I think. Maybe. Kinda. Sorta. Most adverbs and adjectives. Like fillers, they have a tendency to sneak into our speeches without us realizing it.

Teddy Roosvelt hated these qualifiers. He called them “weasel words” because they suck the life out of the words around them. “One of our defects as a nation” he went so far as to say, “is a tendency to use . . . weasel words.”

According to Roosevelt, weasel words make us appear timid and weak. If we want our audience to respect us and listen to what we say, he tells us to avoid qualifiers at all costs.

Ben Franklin, by contrast, was famous for qualifying his ideas. He wrote in his autobiography:

I . . . forbid myself . . . the use of every word or expression in the language that imported a fixed opinion . . . perhaps for these fifty years past no one has ever heard a dogmatical expression escape me.

Franklin would regularly use phrases like I think and if I’m not mistaken. He swore by them.

So who’s right? Roosevelt or Franklin?

The answer is both.

To understand why, let’s jump back to Aristotle for a moment. He explained that credibility is essential to effective communication. We need our audience to believe us and trust what we say.

And when it comes to establishing this connection, context matters. When Ben Franklin was young, he was cocky. He told people exactly what he thought. He’d explain why he was right and they were wrong. And as a result, people thought he was a jerk.

Through much introspection — and feedback from mentors and peers — he developed a more effective approach.

During conversations, he realized there are subtle power dynamics at play. Using firm language like “you need to” and “you’re wrong” upset people. They felt like Franklin elevated his status over theirs, and it drove them away. By listening to the other person’s thoughts, and qualifying his own, Franklin built connections and increased his credibility.

When we help people fully express themselves before passing judgment, they feel empowered and drawn to us. We come to understand the other person’s position and increase the likelihood they will seek to understand ours. When we are on stage, we are not having a conversation. We build credibility with our authority.

By contrast, to connect in everyday conversation, use qualifying language. Focus on empowering the other person. ***

![]() IDEA

IDEA

When you’re on stage, follow Roosevelt’s lead. When you’re in a conversation, channel your inner Franklin.

Practice channeling your inner Franklin today. Try his approach during a conversation. Avoid using any brash and commanding language. Listen fully. Be liberal in qualifying what you say.

***

If you find this useful, please subscribe to our free weekly newsletter.