Talking Big Ideas.

“Memory . . . is perhaps one of James’ greatest gifts.”

~ Total Recall: LeBron’s Mighty Mind

This week LeBron James made history.

With a perfect fadeaway jump shot on Tuesday night, he became the NBA’s all-time leading scorer. (Watch the moment here.) The previous record was held for nearly 40 years by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who wrote a beautiful tribute saying that “LeBron makes me love the game again.”

I’ve never loved basketball, but like LeBron, I did grow up outside Cleveland, Ohio. I stood in downtown Cleveland seven years ago when LeBron achieved another historic milestone: leading our city to its first national championship in more than half a century.

The streets erupted in celebration. Police officers danced alongside inner-city kids as the crowd cheered and cried and celebrated together late into the early morning hours. It ranks among my favorite memories.

I traveled in my mind back to that moment as I read Kareem’s tribute. He called LeBron a hero who inspires millions and praised his “unbelievable drive, dedication, and talent.”

One of LeBron’s most impressive talents is his memory. Journalists have called it superhuman. During press conferences after his games, he can perfectly remember every detail that happened on the court:

This level of “photographic” recall seems superhuman. In the 1940s a Dutch math teacher named Adriaan de Groot recognized a few local chess players that had this uncanny ability. They could play games blindfolded, win, and then remember every move.

Conventional wisdom holds that these players are innately special. But de Groot decided to test this theory with an experiment.

He set up chess pieces on boards to display positions from real games. He gave the players with incredible recall five seconds to view the positions. Their memory was indeed amazing.

Then de Groot ran another experiment. He set up positions on the chess board in a way that the pieces would never appear in a real game. The positions looked totally random to normal players and chess masters alike.

The difference was striking. The chess masters’ memory of these randomized positions was no better than the normal players. Their superhuman abilities vanished.

De Groot – recognized today as a pioneer in cognitive psychology – discovered that what we think of as “photographic recall” is really context-specific excellence in pattern recognition.

Chess masters don’t “think more deeply” than the rest of us. Instead, they recognize patterns and analyze problems more quickly, and “perceive larger and more meaningful units of information at the same time.”

As Daniel Coyle writes in The Talent Code:

The [chess] masters were not seeing individual pieces but recognizable patterns . . . it was a difference . . . between someone who understood a language and someone who didn’t.

Coyle explains that what we think of as “skill” is in large part the ability to read situations and group together seemingly isolated things into a meaningful framework. Psychologists call this chunking.

You are already incredibly skilled when it comes to certain types of chunking. You can prove it to yourself by quickly reading this sentence out loud:

I am more talented than I realize.

Close your eyes and see if you can repeat it from memory. How did you do? Now try the same thing with this sentence:

Ezi laerin ahtde tnel atero mmai.

Can you easily recall it? This sentence is just “I am more talented than I realize” written backwards. But it’s tough to remember quickly because your skill at chunking is context-specific.

You’ve spent years learning how to group individual letters into English words. You’re amazing at remembering these words – which are really just separate chunks of letters – and you even remember groups of words. You likely recalled the sentence above as three chunks (“I am” + “more talented” + “than I realize”) instead of seven isolated words.

Here’s the thing: everyone’s chunking skills are context-specific. You’re not good at recognizing letters chunked together randomly. And chess masters don’t have a photographic recall for basketball – or even for randomized chess patterns.

Look at the two sentences again:

I am more talented than I realize.

Ezi laerin ahtde tnel atero mmai.

The first sentence is analogous to how LeBron James “sees” a basketball game: he can quickly read it with clarity. The second sentence resembles how I see a basketball game.

Your skill at reading English words is like LeBron’s skill at reading a basketball court. These skills have compounded over several years. You’ve gotten so good that it’s easy to forget all the progress you’ve made. The second jumbled sentence helps to drive that progress home.

Chunking works in both directions. We can group individual things into small recognizable chunks – like letters into words – and we can also cut complex things down into small recognizable chunks.

For example, the prestigious Meadowmount School of Music makes students physically cut their sheet music into tiny strips. By chopping complex musical scores down into chunks the students can simply learn each chunk. Playing full songs becomes an easy process of piecing together chunks.

The approach works. Their alumni include many of the best musicians alive: Joshua Bell, Yo-Yo Ma, Kathleen Winkler, Itzhak Perlman, and many more.

When I took violin lessons my instructor was adamant about chunking. Every time I learned a song, I would have to identify the hard measures and practice them in isolation until they became easy. Songs were always divided into chunks, and the hardest chunks got the most attention.

I encourage you to do the same thing with your speeches.

Break them into small sections. Isolate the hard parts: the technical details, the transitions, the opening and closing words. Run reps on these chunks until they’re imprinted in your memory.

Say you have an hour blocked off to practice a 10-minute speech. Don’t run through the whole speech six times. Instead, run through it once and note the hard parts. Then isolate each of them as individual chunks. Pick the hardest and run reps repeatedly until it becomes easy. Then move on to the next one.

Practice your speech this way until all the most difficult and important parts become effortless. You will develop a LeBron James-caliber vision for your presentation.

Come game day, your skill and confidence will help to ensure success.

***

![]() IDEA

IDEA

Divide hard projects into easy chunks.

Consider one potentially difficult sentence you’ll have to say in an important upcoming speech or conversation. Take the time to clarify it in writing. Then break it into chunks and run reps on them until it’s effortless.

***

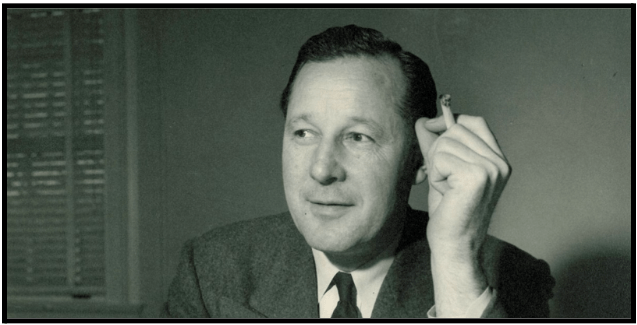

I’ve never met LeBron, but I did have dinner a few years back with Kareem. I’m pretty sure that we’re the same height but he stood on his tippy toes to look taller than me:

For more like this:

Cheers,

Bob

If you find this useful, please subscribe to our free weekly newsletter.